The Klinefelter Cemetery is located at the corners of S. Arlington and E. Nimisila Roads in Green Township, Summit County, Ohio. Dr. Tim Matney was approached by Sarah Haring, Community Development Administrator of the City of Green, at the request of Green Mayor Gerard Neugebauer’s Office in the fall of 2016. The Mayor was interested in delineating the boundaries in Klinefelter Cemetery. In particular, he wanted to install a fence around the historic cemetery but was concerned that many of the headstones in the cemetery had been damaged or removed. At the time, it was difficult to determine the extent of the burials and, subsequently, an appropriate location for the fence.

Prior to its use as a formal cemetery, the land on which Klinefelter Cemetery now sits was a farm owned by Conrad Dillman, who died on November 11, 1834. An Akron Beacon-Journal article published on August 25, 1904 noted that Dillman, “a benevolent and public-spirited citizen of the township” deeded the southwest corner of his farm to the county (then Stark County) as a “free public burying ground” in the winter of 1819-1820 following the death of a poor pioneer named Rhodes, who the article noted still did not have headstone in 1904

The earliest surviving headstone dates to September 8, 1821 and belonged to Susan Wilhelm, again according well with the reported date of 1819-1820 for the opening of a free public burying ground at Klinefelter Cemetery. A survey of the inscribed headstones compiled by Mrs. C. B. Johnson in 1940 noted the presence of Wilhelm’s headstone at that time. Johnson’s inventory was reported in Cemetery Inscriptions, Summit County, Ohio Compiled by the Genealogical Records Committee of the Cuyahoga-Portage Chapter of the D.A.R., Akron, Ohio, February 1957.

The latest surviving headstone belonged to Simon Klinefelter and is dated January 23, 1917. There were 24 remaining stones at the time of Johnson’s survey in the 1940s and all (except Noble) were confirmed in the 2007 survey. Johnson’s 1940 inventory noted that one additional black marker was inscribed but carried no surviving name. Likewise, it noted that there were “fourteen graves marked with plain rocks”. Three possible footstones marked “C.D.”, “E. + G.” and “E.G.” were also present at the site.

Taken together, the following general understanding of the Klinefelter Cemetery can be surmised. Klinefelter Cemetery was founded in 1819-1820 and was in operation for at least a century until 1917. Historical documents and gravestones account for 15 named individuals with known gravesites, two named individuals without headstones (Rhodes and Father K. Hendricks, both named in the Akron Beacon-Journal article) and Perrin’s “other settlers”, some of whom may be accounted for the fourteen graves marked with plain rocks. This suggests a minimum burial population of around 30 individuals, with the likely number buried here to be considerably greater.

Shallow subsurface geophysical surveys were conducted at the Klinefelter Cemetery on two occasions. The first project took place in April of 2017 and the second project took place in May of 2018. During these investigations, a large portion of the cemetery was surveyed using magnetic gradiometry and electrical resistivity. Two techniques were employed: magnetic field gradiometry and electrical resistance.

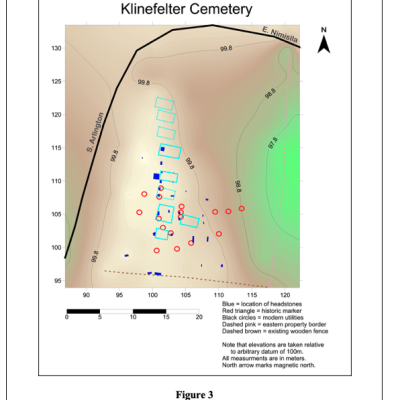

Klinefelter Cemetery is approximately 30 by 25 meters in size. A total of 17 graves were confidently identified within the survey area from the geophysical survey results; more than 15 possible graves were identified for a potential total of over 30 graves. In addition to geophysical survey techniques, Dr. Jerrad Lancaster captured aerial drone photography of the survey area.

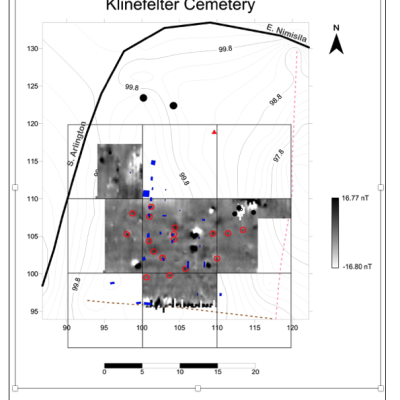

Figure 1 shows the results of the magnetic gradiometry survey. By convention, strongly positive magnetic readings are shown in black and strongly negative magnetic readings are shown in white.

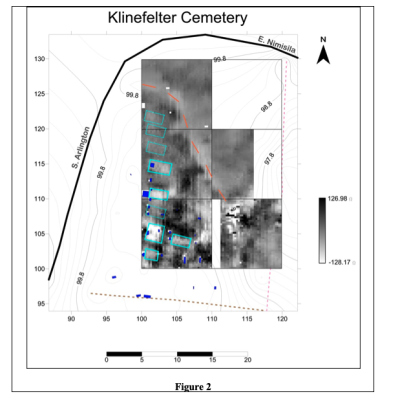

Figure 2 illustrates the results of the electrical resistance survey. By convention, high resistance areas are shown in black and low resistance areas are shown in white. Intervening values are shown in 25 shades of gray.

Figure 3 shows the overlapping results of the surveys conducted by our team and the students at Green High School. In total, we recognized 38 possible graves in Kleinfelter Cemetery using at least one survey method. In some cases (n = 5, 12.8%), especially in the Klinefelter graves, there is a correspondence between the visible headstones, the magnetic field gradiometry survey, and the electrical resistance survey. In other cases, there is correspondence between only two of the data sets (n = 9, 23.1%). The majority of the graves are only seen using one method (n = 25, 64.1%).

In conclusion, it would appear that the preserved graves located in the Klinefelter Cemetery primarily follow the high ridge that runs parallel to S. Arlington Road, as suggested by the extant row of headstones flanking the Klinefelter monument. Although the schematic map from the WPA suggests that the graves were in neat, straight rows running north-south, this is not supported by the geophysical data, although there is a general north-south trend. From the magnetic field gradiometry data, it seems likely that an additional row of graves may, at one time, have existed to the west of the Klinefelter row. This is suggested by two stones and two “hits” in the magnetometry maps. Likewise, there may be a few buried headstones located east of the preserved visible headstones in the lower elevations. The electrical resistance data suggests somewhat convincingly that there were graves following the ridge north of the Klinefelter row, expanding the limits of the visible cemetery for perhaps 10m.